A state of waste

Australia produced 67 million tonnes (Mt) of waste in 2016/17. To speak in the language of Yarra Trams, that’s over 44.5 million Rhinos. Now you might be crunching some numbers in your head and realising that even in your most hedonistic year you didn’t produce 2.7 tonnes of waste by yourself. Well, you’re partially right.

The vast majority of Australia’s waste is created in the commercial, industrial, construction and demolition industries. While this is all generated to provide a 21st-century lifestyle, 13.8 Mt of that total is the municipal solid waste from our households. This equates to 560kg per person of waste every year, simply from what is used at home.

Where did all this waste come from? It seems like only yesterday Nan was using Royal Dansk biscuit tins to masquerade sewing equipment as treats and saving Christmas wrapping to ensure its reuse the following year.

So where does our waste go?

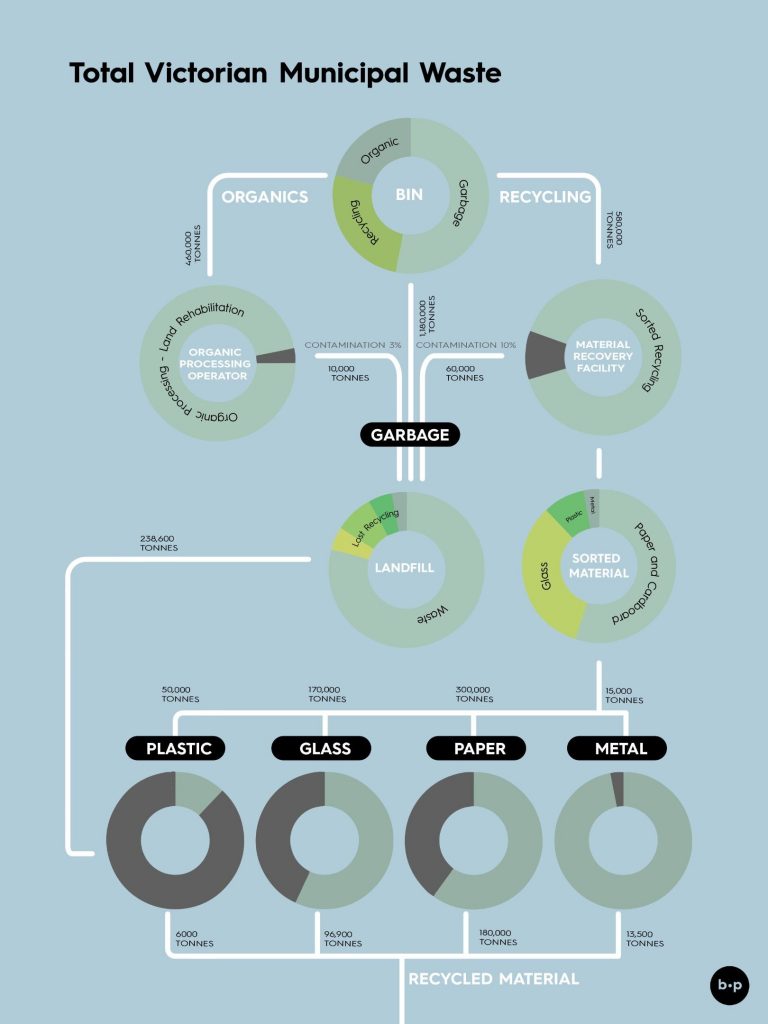

Victoria has the second-highest rate of recycling in Australia, with 72% of our annual total waste by weight, being diverted initially from landfill. This statistic is a little misleading, as such a large percentage of that weight comes from demolition sites being repurposed as road base or commercial organic waste being put into land rehabilitation, soil improvement and urban development.

More than half of Victorian councils operate on a 3 bin system comprising of general waste, mixed recycling and an organics bin. The below graph is an estimate of where it all ends up.

The estimated journey of Melbourne’s kerbside collection waste.

From the household to the landfill

Much of our household waste (1.18 Mt) doesn’t get a chance to be reused and is sent straight to landfill. This is due to contamination, uncollected recycling and unrecyclable goods, like plastic. Roughly 40 per cent of plastics consumed in Australia are single-use: cutlery, food containers, packaging and In 2016-17 Australians used 5.66 billion single-use plastic bags.

However, in metropolitan Melbourne, it’s food and organic waste that makes up around 42% of all waste sent to landfill.

Most households in Australia operate without any designated organic bin. Those few that do, take Food Organics and Garden Organics (FOGO) to organic processors to be screened for contamination and reused as land rehabilitation, soil improvement and urban development. Widespread implementation of Food Organics and Garden Organics (FOGO) system would see the amount of waste heading to landfills drop substantially.

Where does our recycling go?

Piles of rubbish. Photo by Leonid Danilov: https://www.pexels.com/photo/landfill-near-trees-2768961/

The recycling mantra has been a part of everyday life for several decades now and the benefits of reusing materials instead of storing them underground should be fairly obvious. Almost 600,000 tonnes of waste ends up in our recycling bins and is either sorted in a local recycling plant or in a Material Recovery Facility (MRF). These facilities sort through mixed recycling from our yellow top bins. Uncontaminated materials are then sent to specialised facilities to be remanufactured, reused, exported or used in “Alternative Waste Technologies”.

A good example of alternative waste technologies is an Energy from Waste plant (EFW). These plants burn collected waste and capture the released energy to generate power or heat cement kilns. Sweden famously has a 100% recycling rate (compared to Australia’s 42% and USA’s 47%) and imports waste from European countries to keep their EFW’s running. Statistics will show they send 0% of waste to landfill, however this statistic is generally only for direct landfill. Incineration reduces the weight of materials by 66%, meaning out of every tonne of waste burned, 333kg is still eventually sent to landfill.

While EFW’s are not widely utilised in Australia, they are considered to be a great solution to mounting recycling troubles. These types of methods bring a lot of ambiguity to the definition of recycling. They’re preferable to direct landfill, however incineration often happens too early in a material’s life cycle and all of its potential for reuse is lost. EFW’s reduce the cost of waste disposal and increase our recycling substantially, but aren’t a great long-term solution.

Australia lacks the infrastructure necessary to process the amount of recyclable waste it produces. However in the 2020 federal budget Josh Frydenberg announced that the government would ban the export of plastic, paper, tyre and glass waste and invest $250 million on recycling infrastructure.

The funding is designed to support the government’s target of 80 per cent diversion from landfill by 2030 and includes $190 million for a new Recycling Modernisation Fund. A further $24.6 million to improve waste data and $35 million to support the National Waste Policy Action Plan.

It is estimated that this funding will divert over 10 million tonnes of waste from landfill.

Selling and storing our recycling

It’s easy to assume that so long as you rinse your containers, separate your soft plastics and so on, whatever you put in that yellow bin is going to be recycled. Unfortunately not.

Excess recycling generated in Australia is exported, primarily to China and Southeast Asia. Until recently, this had been a financially sustainable and profitable business model as recycling was sold to subsidise our own waste collection services. In 2017 China changed its quality regulations which caused paper, cardboard and plastic recycling exports to nosedive. Operation National Sword was the change to China’s regulations requiring recycling imports to contain below 0.5% contamination. This effectively placed a ban on over 100 countries who had been happily sending their waste off in ships to be processed elsewhere.

Australian plastic exports fell from 10,000 tonnes in January 2017 to 400 tonnes in just one year. Scrap paper and paperboard exports also fell from 88,300 tonnes to 42,800 tonnes in the same time period. Recycling is a commercial industry that only survives when there is money to be made. With half the world suddenly finding themselves with an abundance of recycling waste, prices dropped through the floor.

How can I recycle better?

So in this world of global politics and struggling infrastructure, you might be thinking how, if at all, can the average person help? Victorians have read the writing on the wall for quite some time and are already heading in the right direction. Despite a 34% increase in population since 2001-02, the total amount of waste generated by Victorians has only increased by only 7%.

Public awareness has never been higher but there are still more ways in which we can help effect change.

- Avoid products with excessive or unnecessary packaging and buy recyclable items and products that include recycled materials.

- Understand the principles of circular economy and reuse or repair items, instead of replacing them.

- Purchase higher quality items that will last. They may be more expensive, but their quality and impact on the environment make them worth it.

- Improve recycling habits by sorting waste properly at home to reduce the stress on government sorting systems. Utilise existing recycling initiatives like separating soft plastics and depositing them with Redcycle at Coles and Woolworths.

What can we do to reduce waste?

Recently, ministers agreed to set a target that all Australian packaging be recyclable, compostable or reusable by 2025 or earlier. While this was seen as ambitious, the European Commission is going as far as planning to phase out plastic cotton buds, cutlery, plates, straws and single-use plastic bottles with detachable lids. Europe is also trying to shift responsibility from consumers to producers for their products entire lifespan. This means it would be the responsibility of the producer to manage their products disposal as well as production.

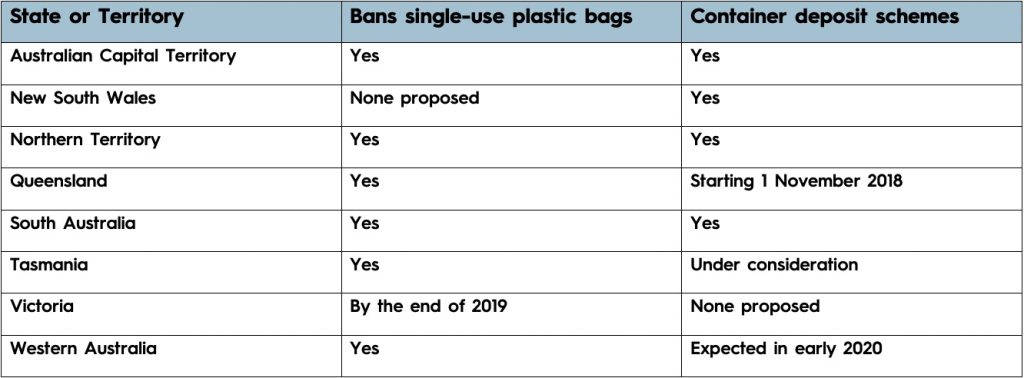

Recent pressure on governments through this public awareness has also seen new waste reduction initiatives taken up across Australia:

Table 2.0 Sustainable initiatives being pushed or recently introduced.

As Australians begin to look long term at our waste and recycling, the hope is more facilities will open domestically which will improve our domestic recycling recovery capacity. A great deal needs to change at the infrastructure spending and political level to cope with rising population and waste generation.

At ground level, the most powerful way to effect change is to alter our culture and our relationship with waste. Once we generate and dispose of waste rubbish, we have very little say about what happens to it. So taking responsibility for the waste we create and creating systems that promote not just recycling but reuse will ensure that products we use don’t survive longer than we do as waste.

These improvements will be critical for a sustainable future, as we further advance into an age of finite resources and vast technological advancements.

See more in our episode ‘Sustainability & Real Estate’ where we speak to three local experts and gain fresh insights into sustainability and waste.

Words by Joe Hoppe for blueprint