Is urban farming the answer to Melbourne’s growth?

Ah, Victoria. The garden state.

Home to Old Melbourne Town, artfully masterplanned as a compact city. Known worldwide for great coffee, year round sporting events, a vibrant theatre scene and of course the street art.

But Marvellous Melbourne’s not-so-marvellous urban sprawl now regularly competes with the likes of Los Angeles and Mexico City. We’re also on track to be home to 8.5 million people by 2050 and despite efforts to control our urban boundaries, are continuing to swallow farm land like never before.

Given the constant pressure on our foodbowl, could urban farming be the answer?

What’s urban farming?

Any of us that endured Melbourne’s lockdowns in 2020 (apparently a world record) likely tried some form of gardening. While we were the household that struggled to keep a Bunnings succulent alive, our neighbours built their own chicken coop.

Farming – or producing anything edible – inside an urban area is sometimes loosely referred to as urban farming. It can be anywhere from rooftops to car parks, nature strips or even school yards.

However, technically urban farming only refers to a commercial venture, as opposed to the backyard chook shed or local community garden.

It can include growing fruits and vegetables, raising livestock, beekeeping or even making value adding produce such as preserves, as long as they are on sold (including not for profit) as opposed to being consumed by the producer.

History of urban farming in Melbourne

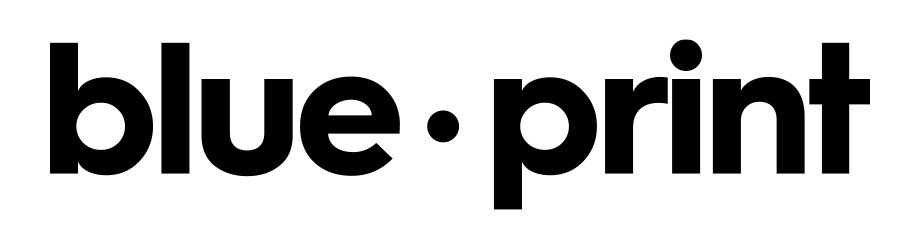

In 1942, Australia’s PM John Curtin famously launched ‘Dig for Victory’, urging homes to grow food to fight off any potential food shortages from WW2.

Dig for Victory was a successful campaign, which resulted in annual import foods were halved to 14.65million tonnes by 1941. Images by Peter Mackiln & Adrian Brooks.

As a result, ornamental gardens throughout Melbourne started to include areas used for food supply. Mansions such as Rippon Lea Estate in Elsternwick repurposed their landscaped lawns so they could be used as productive gardens.

And as recently as last year, Werribee Park teamed up with a local Sikh temple to replace their florals with vegetables. The produce was then donated to various community kitchens to assist locals struggling with the impacts of COVID-19.

City of Melbourne has supported street gardening, especially for restaurants and cafes that have sufficient space in their nature strip, as long as they comply with the 2015 Street Garden Guidelines. They also helped establish the Kensington Stockyard in 2018, which produced fresh produce for various charities.

So why hasn’t it taken off?

Melbourne’s blessed to be surrounded by highly productive regions that grow most of Victoria’s vegetables and a good chunk of its fruit too.

A 2016 study published by Melbourne Uni found that 41% of Greater Melbourne’s food needs are currently serviced by farms on its urban fringe. This excludes other large regional towns in Victoria, making us virtually self sufficient for most of the staple foods.

Other, more practical issues with urban farming have historically led to most people dismissing it as just another fad:

“It’ll never be enough to feed an entire city.”

Centuries of research, particularly during the 1900’s with the ‘green revolutions’, have established industrial agriculture to be far more productive. Sure, ramping up production in the last century took more chemicals, so bringing the organic produce angle into urban farming could be interesting, but in terms of scale it’s almost impossible to compete.

“It’s not even more environmentally friendly.”

Here’s the irony – that small veggie patch in your backyard is likely taking up way more water, fertilisers and pesticides per square metre, just to get going. Even if the soil you’re buying from Bunnings is organic, the embodied energy to bring it to an urban area is massive. And indoor or vertical farms take up so much energy (such as artificial lighting) that it can be borderline counter productive.

“Miles don’t matter as much as we think.”

The ‘Food miles’ policy is a concept that looks at reducing the distance a product travels to market from the production source. They think by shrinking the distance, the positive impact to the environment would be huge.

However, research from academics at USC and Purdue has shown that transport is in fact a relatively small proportion of the carbon emissions associated with food. Things like processing and packaging methods were the real issues, as opposed to the point to point transport, with the exception of those transported by air.

Should we still bother?

The COVID-19 pandemic brought attention to issues with international (and even interstate) supply chains and impacted consumer wallets like never before. Panic buying in supermarkets and butcher shops also highlighted the risk of food security.

Researchers in the UK have argued that urban farming can assist in creating more resilient food supplies, by increasing the diversity of sources to mitigate any future disruptions.

The 2016 study by Melbourne Uni also found that Melbourne’s foodbowl capacity to feed our city could fall down to as low as 18%. Areas from Bacchus Marsh in the west to even Yarra Valley in the east have been at serious risk for quite some time, owing largely to pressures from a rapidly increasing population sprawling into these areas.

Where Melbourne’s food comes from. Image by Melbourne University.

Farmers are ageing rapidly, with those nearing retirement age now relying on selling the farms so they can fund their retirements. The buyers have little to no commercial incentive to set up any farming there, despite the favourable (and ready to go) soil conditions, and usually end up going down the same old route of low density housing estates.

Environmentalists also concede that although urban farming may not be a clear cut answer from a sustainability perspective, it does help in creating healthier and more diverse habitats. Urban areas can sometimes support larger scale pollinator populations than the wider countryside.

And creating more visibility of urban farms can help in healthier food choices, as evidenced by the ever growing farm to fork trend across our restaurants. People who participate in community farming learn what it takes to grow food and end up appreciating the benefits of following seasonal produce.

Examples of Urban Farming in Melbourne

Farmwall

Farmwall brings urban agriculture to the city through vertical farms. Originally created to be set up on skyscrapers, it’s since expanded into cafes, restaurants and office spaces.

Their flagship design is an aquaponic inspired system that grows fresh produce. Higher Ground in the CBD and Top Paddock in Richmond are among those already using this tech.

The Ecosystem Indoor Farm also encourages households to grow their own food and nutrition. Photo by Farmwall.

Honey Fingers

Honey Fingers is a beekeeping collective based in Melbourne’s inner north. Their hives are located in various domestic gardens and produce over multiple varieties of honey.

The honey from each suburb has a distinct flavour and is never mixed together. Post harvest, each unique flavour is sold through bakeries and cafes around town.

Cultivating Community

Cultivating Community helps over 700 gardeners maintain community gardens across Melbourne. Their gardens not only increase local food security, through increasing access to food and food literacy, but also bring communities together.

Melbourne Skyfarm

A 2000 square metre rooftop car park into an urban farm and environmental oasis in the heart of the city.

Visitors will be able to tour the working farm, visit the orchard, sample honey, dine at the sustainable café and attend classes at the environmental education centre.

The productive Garden State

It’s a romantic notion to think that urban farming and community gardens can feed a population – or even sustain small community, but maybe that’s not the point. If as a city we gain a better understanding of how to grow food and we increase the education of food production, we will be better in the long run.

Because through urban farming we might create a generation of Melburnians that not only understand how food is grown and have greater appreciate for farming but maybe we can even inspire them to become involved in farming and lead us to innovative and resilient food growing future.

Community gardens are important to help educate young people about growing food. Image by suriyachan.

At the end of the day, only cities that are nimble enough and recognise this need are likely to survive the climate change battle.

We need to be the productive garden state.

Check out Making megacities healthy for humans.

Words by Raghav Goel for blueprint