Should we tear down Melbourne’s public housing towers?

With the recent hard lockdowns of eight public housing towers in inner-Melbourne due to COVID-19 outbreaks, attention has turned to these iconic buildings. Many Melburnians pass them daily without a thought as to who lives there and why, and what the living conditions are like.

There are 47 public housing towers across 19 suburbs, and although they’ve become as prominent to Melbourne’s inner city aesthetic as terrace houses, they‘ve been the elephant in the suburbs until now.

So with the new found and most likely temporary spotlight, could there be winds of change coming?

Exploring the exciting realm of Australian online casinos has never been more exhilarating, especially with platforms https://online-casino-au.com/online-casinos/ezeewallet/ that offer eZeeWallet casinos. At our comprehensive review site, we focus on helping Aussies find casinos that are not just entertaining but also safe and secure. Our recent spotlight has been on ezeewallet casinos, highlighting their rapid, user-friendly transactions. But if you’re looking for a change of scene from the digital casino floors, dive into the heart of Melbourne with our favourite group of Melburnians! They’re passionate locals, sharing unique tales, hidden gems, and vibrant commentaries about this beloved city. Merge your love for online gaming with a virtual stroll through Melbourne’s bustling streets and rich culture!

Why were the towers built?

Public housing in Melbourne began in 1937 with an aim to provide adequate housing for persons of limited means.

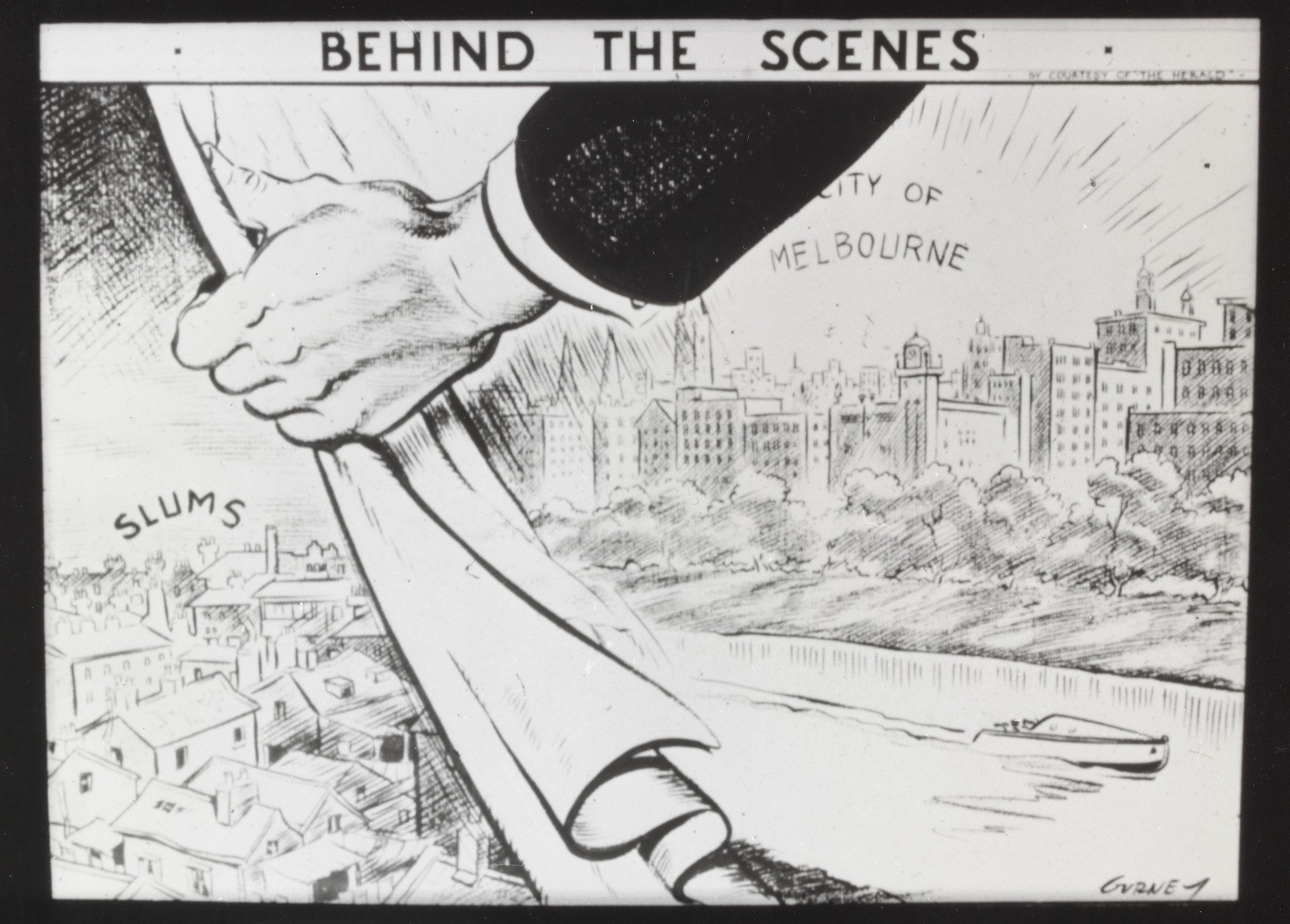

Initially focused on clearing ‘slum pockets’ where residents lived in squalor during the Great Depression, things took a dramatic turn in the 60s and 70s, arguably taking cue from claimed success in the communist world.

The slums behind the public face of the City of Melbourne. Source: State Library Victoria

“The high-rise model was seen as a cost-efficient way to deliver a large number of dwellings on plots of land that the government owned. That logic hasn’t changed very much.” – RMIT urban development Professor Libby Porter, speaking to ABC Radio Melbourne.

Melbourne built more than 40 towers across 19 suburbs during the ‘communist era’, in a similar fashion to those being built in the Soviet Union.

What are they like now?

Although we now have more evolved models of social and affordable housing (such as those provided by community groups), the quality of most inner city public housing towers is quite abysmal.

A 2018 Victorian parliamentary report confirmed the poorly insulated and overcrowded towers were the result of years of chronic under-investment.

Some of the public housing towers have also long been blamed for a wide range of social issues, with known epicenters of drugs and noticeably higher crime rates among the complexes.

On July 5, acting Australian Chief Medical Officer Paul Kelly referred to the towers undergoing coronavirus lockdown as “vertical cruiseships”, a reference to the danger of contagion in these buildings.

Public Housing Tower in Collingwood. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Should we just get rid of them?

It’s a controversial thought to say the least. After all, we’re talking about real people and their homes.

However, Victoria’s Public Tenants Association estimates there are 100,000 people on waiting lists for public housing, so change is well overdue.

The business case to demolish the towers has been supported by two broad redevelopment options:

- New higher quality public housing on the site at a greater density; or

- Relocating the public housing elsewhere (but again at relatively high density) and using the land for private dwellings, with potential for affordable housing components.

Both options make sense. High density, say academics from the University of Melbourne, is not the problem – it’s the way such buildings are designed, maintained and funded.

The state government received praise when they added new modern high rise buildings to the public housing in Richmond back in 2013. They stand at a stark contrast to the majority of other badly aged towers there which are constantly in the news.

But Melburnians are legendary NIMBY’s (let alone when it comes to public housing) and relocating society’s most vulnerable to the outskirts has proved to be a tall order for even the highest paid spin doctors.

Public housing towers in Fitzroy in the 1960s. Photo: State Library of Victoria.

Enter Retrofitting

Definitely the quicker, more sustainable and probably the less capital intensive option, retrofitting the towers has been suggested as a simple and high impact solution.

In some cases, it could even allow residents to keep their homes.

Too good to be true? Not at all, because the Europeans have already succeeded in the experiment.

The restoration and retrofitting of 530 apartments at Grand Parc Bordeaux in France is shining example. The 1960s social housing block added deep winter gardens and open air balconies while replacing lifts and renovating hallways, all without displacing residents.

A massive housing block in the Netherlands was set for demolition before a protest sparked an award-winning renovation. Only the main structure of the 1960s block was renovated so that the residents could customise the their apartments based on their needs.

In Sheffield UK, the Park Hill Estate is similar to our towers in that it was built post war, is very visible and is very much part of the popular consciousness of the city. It too escaped demolition, but only the concrete frame actually remains with the rest of complex completely gutted.

Park Hill council housing estate in Sheffield, England. Photo: carlip_ivor

So what’s our plan?

The Victorian Government has released a suite of initiatives aimed at increasing the range of housing assistance and the number of social housing properties in order to address the shortfall.

The biggest being the $5.3bn towards building 12,000 social housing homes throughout Melbourne and regional Victoria. This investment is said to include the replacement of 1,100 existing public housing units. How and when remains to be seen but more detail is set to be released in the state budget.

There is also $1 billion Victorian Social Housing Growth Fund, which will construct new social and affordable housing on non government land such as those part of private developments.

Under the proposal, the state-run dwellings would be mixed with private housing and homes managed by community housing providers. The mixed developments are intended to avoid many of the problems, such as social stigma and community isolation.

A further $185 million has been earmarked towards redevelopment of eight existing public housing estates as part of the Public Housing Renewal Program.

The chosen estates are in North Melbourne, Heidelberg West, Flemington, Brunswick West, Brighton and Northcote.

The development plan for the North Melbourne estate was released on October 13, which included an increase in the number of social housing dwellings by 21 and between 135 and 235 new private dwellings.

The aim is to build 133 social housing dwellings (there is currently 112) including 47 one-bedroom, 80 two-bedroom and six three-bedroom.

The design intent of the project is to provide high-quality social and private housing that integrates seamlessly into the existing fabric of the area and is tenure blind to the public realm. – North Melbourne public housing renewal development plan.

City of Melbourne recently announced a ’land sale and development’ agreement to deliver more affordable housing and even suburban councils such as Knox in the outer east are actively moving to a public private model.

However, in most cases the public private model is looking at at least 3-5 years to deliver and seeking to demolish instead of retrofitting.

So despite the success seen in Europe and extensive research to prepare guides, ironically Australian government initiatives, there seems to be a lack of will among all levels of government to take up this challenge.

Perhaps in the light of the drastic actions during COVID-19, we might hold our governments more accountable to their immediate responsibilities towards our fellow Melburnians.

Words by Penny Barker and Raghav Goel for blueprint