Australian Modernism’s Top 10: Part One

Australia’s modernist movement had an enormous impact on the urban and cultural fabric of our country throughout the 20th century.

Its impact is felt far and wide, informing the design of everything from household objects and furniture, to the local swimming pool and the iconic Sydney Opera house.

It has transformed our art and design, our houses, infrastructure and urban spaces.

London’s much-celebrated Isokon apartments, also known as the Lawn Road flats. Picture: Getty Images

Modernist design ushered in a new way of thinking, leaving behind the historical styles of the Victorian era and prioritising the pressing needs of a new, rapidly growing nation.

Strong shapes, geometric forms and clean lines came to the fore in the decades before World War II and went onto evolve in a multiplicity of expressions through to the 1970s. Innovations in construction methods saw glass, steel and reinforced concrete used in ways never seen before.

Modernism in all its guises, heralded the creation of some of Australia’s most recognisable examples of architecture and design.

In part one, architectural historians Hannah Lewi and Philip Goad delve into this rich architectural legacy to choose their top well known and hidden gems.

Sanitarium Health Food Company Factory

Design: Edward Fielder Billson

Constructed: 1936-37

Location: Warburton, Victoria

Professor Hannah Lewi: Situated in the picturesque town of Warburton east of Melbourne, the former Sanitarium Factory is a tangible reminder of a lost faith in local manufacturing.

In 1940, it was awarded the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects Street Architectural Medal which was the first recognition for an industrial building and one outside of Melbourne.

Influenced by the Dutch Modernist Willem Dudok, the building consists of striking cream brick horizontal and vertical elements with bands of steel framed windows, blue glazed bricks and a tower complete with a large clock. With the Signs Publishing Factory next door, the site is set in a forest landscape, reflecting ideas of self-sufficiency and workers amenity.

Sanitarium Health Food Company Factory in Warburton was recognised for its design. Picture: Christine Francis

It survives today, protected by recognition on the Victorian Heritage Register, but still looking for new and viable uses.

Cairo Flats

Design: Taylor, Soilleux & Overend

Construction: 1935-36

Location: Fitzroy, Melbourne

Professor Philip Goad: Cairo is a two-storey, U-shaped block of tiny bachelor flats in Melbourne’s inner suburb of Fitzroy designed by Best Overend

He had returned to Australia from London where he had worked for modernist architect Wells Coates on the much-celebrated Isokon, also known as the Lawn Road flats, in 1934. These flats were home at one time to émigré architects Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy, as well as the crime-writer Agatha Christie.

In Melbourne, Cairo was the same: a modernist icon and home at one time for architects Frederick Romberg, John Mockridge and others in the 1940s.

Decades later, I endured its existenz-minimum interiors. But I loved its rooftop overlooking the Exhibition Gardens, its daring cantilever concrete stair and its wonderfully large central garden – an oasis of peace and greenery just steps from the city.

Today, it still retains all the excitement and relevance of a new and modest way of living.

The Cairo is a two-storey, U-shaped block of tiny bachelor flats. Picture: Christine Francis

Woomera Village

Design: Commonwealth Department of Works and Housing

Construction: 1946-67

Location: South Australia

Professor Hannah Lewi: Undoubtedly the most remote example in the Australia Modern list, the isolated village was designed to create a community around the Australian Long Range Weapons site in South Australia.

The scheme planned and constructed prefabricated housing for service personnel, workers and their families along with landscaping and amenities including a school and a theatre in an attempt to mitigate the harsh living conditions.

Woomera was designed to create a community around the Australian Long Range Weapons site. Picture: State Library of South Australia

Striking images from the period of Woomera’s heyday picture a relentlessly red, dusty place only punctuated by green sporting ovals and a planted greenbelt from locally established native trees.

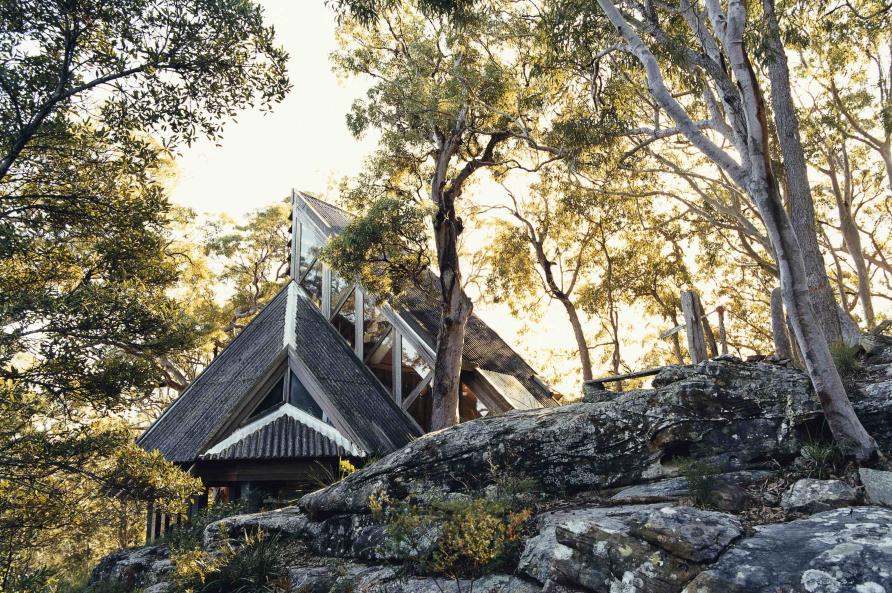

LOBSTER BAY HOUSE

DESIGNER: IAN MCKAY

CONSTRUCTION: 1971-72

LOCATION: PRETTY BEACH, NEW SOUTH WALES

Professor Philip Goad: Rarely seen and little known, even within the architectural profession, this house designed for the photographer David Moore is one of Ian McKay’s best residential designs.

Lobster Bay House is one of Ian McKay’s best residential designs. Picture: Michael Wee

It incorporates a series of geometrically derived shed-like forms that nestle comfortably into a startling rocky landscape by the sea.

One of Australia’s unsung modernists of the humanist kind, Sydney architect Ian McKay’s early work was strongly influenced by the organic principles of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture.

By the late 1960s, he had extensive experience designing housing and housing estates for the National Capital Development Commission in Canberra.

With this experience, he became vocal in advocating for better quality in residential design across all scales, publishing the seminal survey, Living and Partly Living: Housing in Australia in the same year that Lobster Bay House was under construction.

Beaurepaire Centre

Design: Eggleston, MacDonald & Secomb

Construction: 1954-57

Location: University of Melbourne, Parkville campus, Melbourne

Professor Hannah Lewi: The Beaurepaire Pool and Gymnasium is a highly awarded example of modern architecture and art, united to create a special place in the lead up to Melbourne hosting the Olympic Games in 1956.

The pool was instigated and sponsored by the businessman, politician and swimmer Sir Frank Beaurepaire.

The architects collaborated with the engineer Bill Irwin who also worked on the Sidney Myer Music Bowl and the Melbourne Olympic Swimming Stadium to design a glazed, light-filled enclosed 25-metre pool and sporting facilities.

The Beaurepaire Centre was built in the lead up to Melbourne hosting the Olympic Games in 1956. Picture: University of Melbourne

They also worked closely with the artist Leonard French, who created a striking mosaic-tiled frieze around the building’s exterior facades and the colourful, abstract mural Symmetry of Sport for the upstairs gym and trophy hall.

The complex was sensitively restored by Lovell Chen with an award-winning upgrade in 2003.

Written by Professor Hannah Lewi and Professor Philip Goad and first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

Banner: Beaurepaire Centre/Christine Francis

You may also like our Q and A with Hannah Lewi on Australian Modernism