What the Small Homes Service can teach us today

In post-war Melbourne, it was possible to open The Age and scan a weekly catalogue of architecturally-designed homes, drop five pounds on the weekend at Myer Bourke Street to purchase the blueprint of your favourite, and hire a builder to start on Monday.

Called the Small Homes Service, the program by Royal Victorian Institute of Architects was initially directed by Robin Boyd and ran from 1947 to the late 70s. It offered returned servicemen, new migrants and the broader public the opportunity to own affordable and innovative modernist homes in Melbourne’s suburbs.

In a time where Melburnians are confined to their place of residence, we have a new opportunity to think creatively about the realm of the home and do better with less.

So what can the Small Homes Service teach us today?

Our suburbs deserve good design too

A key aim of the Small Homes Service was to democratise good design. It achieved success by using some modernist principles of simplicity and clarity, but largely focused on providing an individual identity to each home that appealed to the people’s needs.

By providing an aspirational option in post-war boom times, the designs are a stark contrast to the cookie cutter french provincials or tuscan villas offered by builders today.

Melbourne’s suburbs from Kew to Oakleigh to Beaumaris would look vastly different if it wasn’t for this program, but the same suburbs are today at risk of being the Australian ugliness Boyd mooted during his time.

The OG of tiny home movements

#cabinporn had been trending on Instagram for a while before accommodation startups made it possible to experience off-grid, well-designed, eco homes for a weekend. These services recognised our growing itch to decouple from the busy city – to simplify, and see if we could do more with less.

But well before it came the Small Homes Service. And around the same time came the golden rules the program made mainstream – economical use of space, good solar orientation, maximised living space and connecting with the local surrounds.

In most cases, they took up a small portion of the block so the homes could be naturally responsive to the prevailing landscape.

The idea of a prefabricated, sustainable, small house allows us to design a life where we work out how little we need to live well, with minimal impact on the environment.

Perhaps well-designed prefabricated and modular tiny homes are an antidote to a hyper materialistic society in which personalisation and customisation are par for the course. As we grapple with climate concerns, economic uncertainty and the idea that a city may no longer be a central force in our work and social lives, moving closer to nature – literally and figuratively – might have increased appeal.

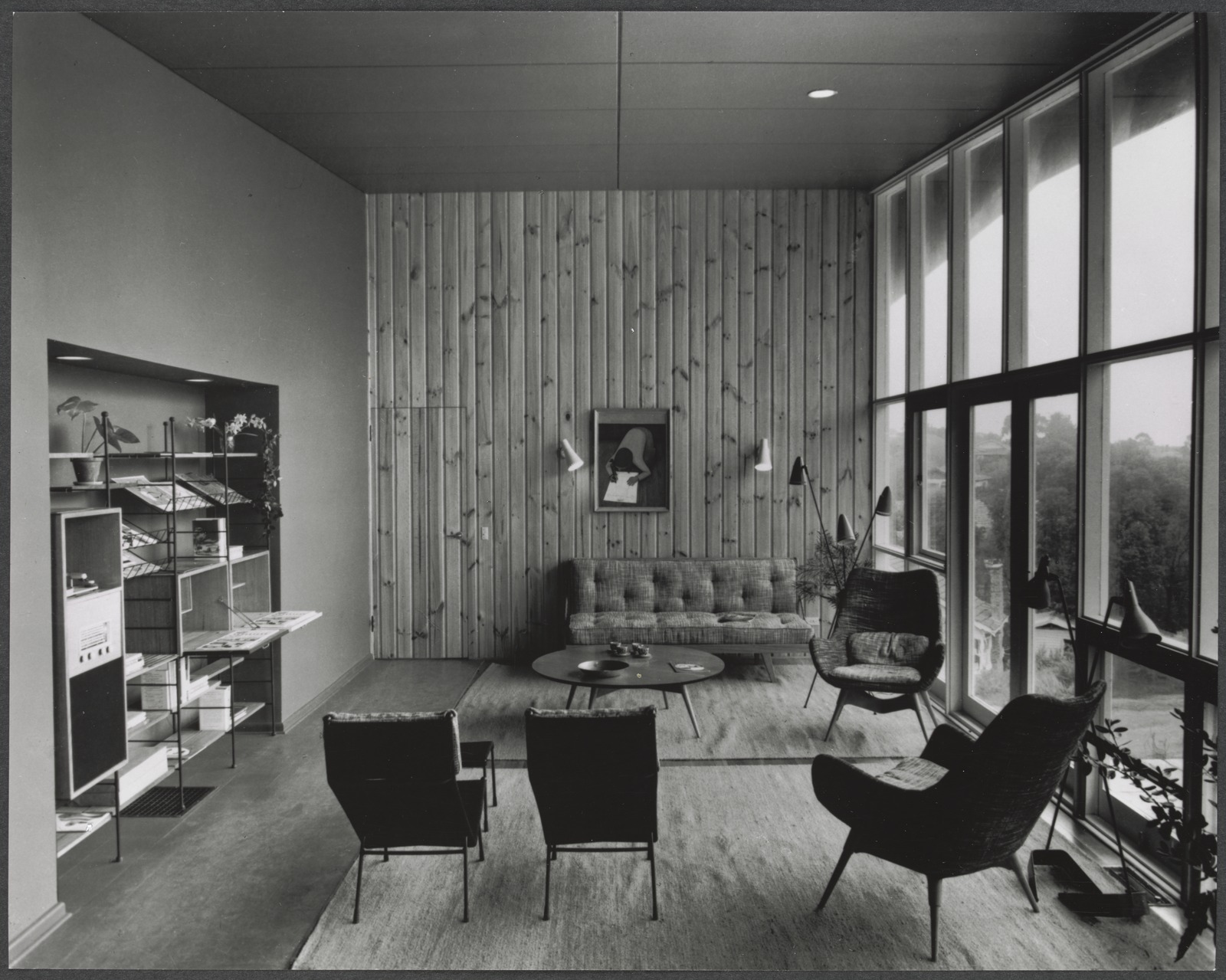

Age Dream Home, Union Road, Balwyn, 1955 (demolished). Designed by the RVIA Small Homes Service in conjunction with ‘The Age’ newspaper.

Connecting with each other

The Small Homes Service is from a time when land was considered in shortage, but was in fact aplenty and austerity was no longer required, but was still practiced. The program encouraged people to “do better with less”.

Today, land really is even less finite and our true needs are being tested by the impacts of COVID-19.

Still, our suburbs are giving way to cookie cutter townhouses by non-architect designers that just aim to tick the ResCode provisions, instead of re-imagining communities that allow the social connections we need.

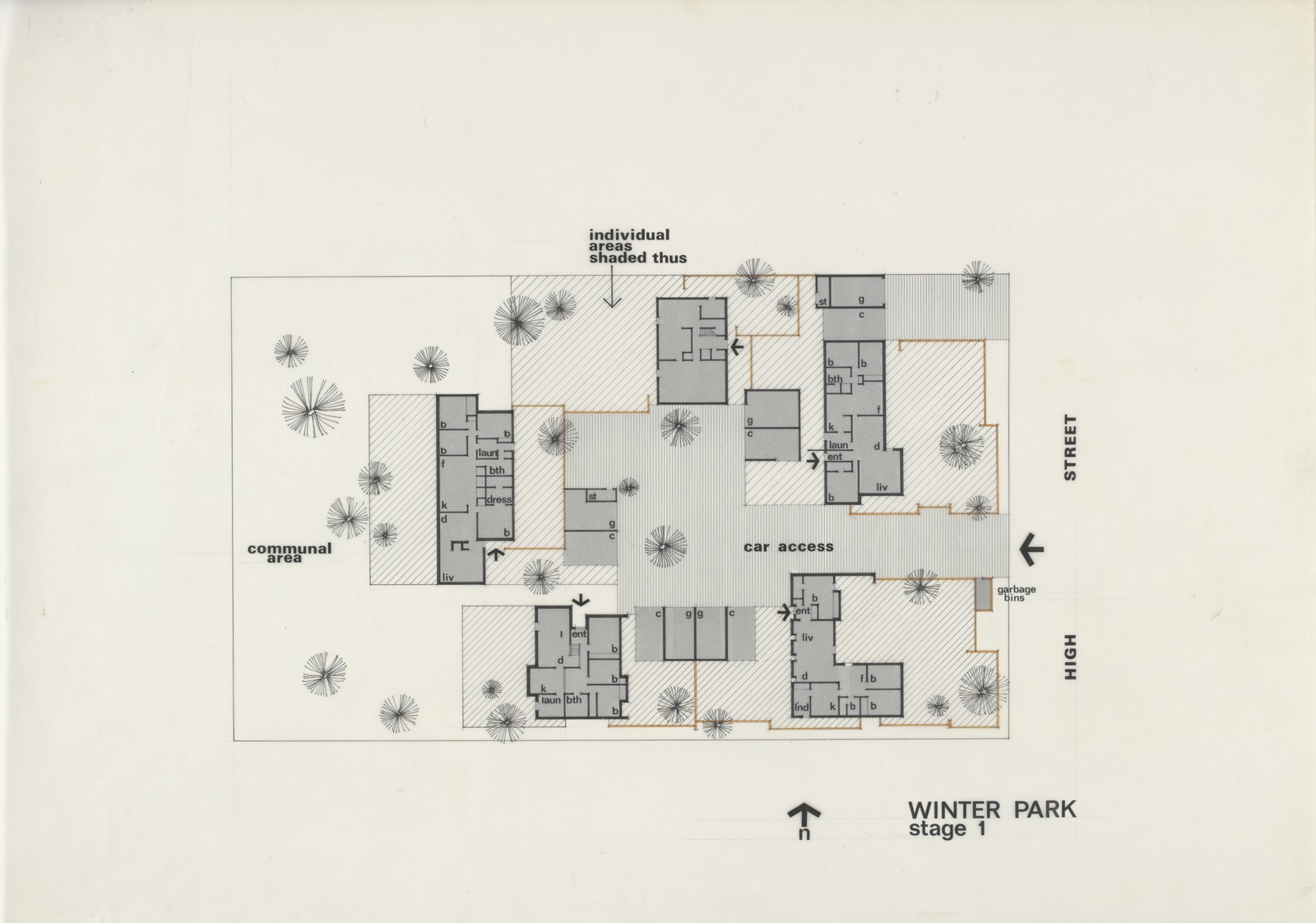

Micro-communities – clusters of houses that are self-supporting and productive are hardly a new idea. Boyd himself achieved this in his clustered housing projects, alongside the likes of Merchant Builders in their own versions throughout the 60’s and 70’s.

Built in the 1970s, Winter Park Doncaster is a carefully planned development in which the houses are sited to optimise available land. It features communal car and pedestrian access ways with a large central communal recreation space. Photo: State Library of Victoria

But the version today could be where cars are shared, with fewer needed. Garages could then be turned into communal workshops or co-working spaces. Fences could be knocked down to create semi-public spaces with shared facilities greater than what the individual owner could realise.

Multiple generations could be supported and brought back together.

In this scenario, good design could overcome the constraints of the suburban block and enable new ways of living.

A small home in Surrey Hills Designed by the RVIA Small Homes Service in conjunction with The Age newspaper. Photo: State Library of Victoria.

A sprawling legacy

A crude equivalent of the Small Homes Service is the McMansion offered by volume builders today.

However, instead of being a service to the community, these builder homes have a sole purpose of reducing costs and streamlining delivery.

Nevertheless, in many ways the Small Homes Service assisted as a pathway for this sprawl and the beacon is being carried forward with less magnanimous intentions.

With greenfield suburbs popping up everyday, Melbourne’s sprawl is now infamous – comparable to Los Angeles and Mexico City – and possibly the biggest learning from the Small Homes Service would be to not repeat it in the same form again.

Words by Katia Greenwood and Raghav Goel for blueprint

Watch the modernist design movement’s influence on Melbourne in our episode Why does Melbourne look like this?